Last week Haaretz published an extensive article on Dr. Nyman Levin, director of the British nuclear weapons establishment in the 1960’s and someone that may, or may not have been, a spy, leaking nuclear secrets to Israel.

The two authors, Professor Avner Cohen from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey and Meirion Jones, the investigations editor at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London, mentioned in their article that: "the British government firmly refuses to confirm or deny whether Levin was under investigation [on suspicion he was leaking nuclear secrets to Israel]. Indeed, the British government fought the authors tooth and nail to prevent the release of any relevant files about Levin".

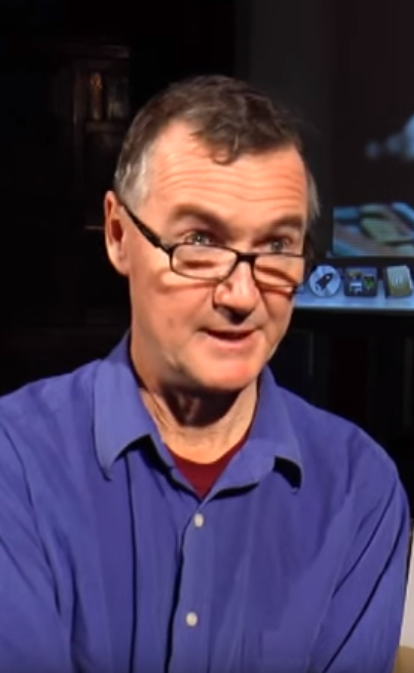

In order to understand a bit more how the British government fights to keep its nuclear secrets far from the public, Meirion Jones joined Kol-HaAyin radio program and spoke with hosts Oren Persico and Adi Noy. Below is an edited version of their conversation.

When did you first learn about Levin and the suspicion he was actually a spy leaking nuclear secrets to Israel?

“In Britain, the Freedom of Information law only came into effect in 2005. I got all sorts of Freedom of Information requests in on all sorts of subjects and one of those was Britain and its connections to Israel’s nuclear program. They always denied there was any connection whatsoever, but that first year they didn’t check very carefully what information they released. So I had huge numbers of documents released. They would have looked very boring to a bureaucrat, but if you dug through them you could find that Britain had exported heavy water to Dimona, some Plutonium, Uranium, and I published a piece in The NewStatesman and also in the NewsNight program about all this.

“The really key thing was that they had not redacted any of the names of the people on these reports from the early 1960’s, and I found people who were still alive, at that point 40 years later, who I could then talk to and get more details. One of those was the person who first realized a nuclear reactor was being built at Dimona, Peter Kelly from the British Defense Intelligence. After we did that first story he imagined that if the government was allowing that sort of information out they would allow everything out. So he said to me ‘You need to ask some questions about Nyman Levin. There were three Jewish scientist being investigated, two of them were cleared, one of them was Nyman Levin, before they got to the end of the investigation he dropped dead in the Cabinet Office’.

“Now that sounded like a fascinating story to me so I immediately started digging in to it, and in the course of all that, once I established that he had a catastrophic heart attack in the Cabinet Office and had died a couple of days later, that he had just been released of his job as day to day head of the atomic weapons program in Britain, I put in a lot of Freedom of Information requests”.

And did receive any answers to those requests?

“Well, the Cabinet Office responded to me eventually saying ‘we can’t give you any information about this at all, and we are not going to’.

The process in Britain is that you then appeal internally first, and I got nowhere with an internal appeal, then you go to someone who is called the Information Commissioner and he came up with a ruling which said they were entitled to keep the file secret but they had to tell me what they had. They had to tell me if they had an investigation file on Nyman Levin. The Cabinet Office said they were not even going to tell me whether there was a file, whether there was an investigation let alone what came out of it”.

“It’s a very long process in Britain, the whole process took years, but in the end of the road it’s then appealed to something called the Information Tribunal. I then expected to appear at the Information Tribunal and make my case, but the Cabinet Office said I could not be allowed to appear in that hearing, it would have to be the Information Commissioner, who did not have as much information as I did.

"The Information Commissioner and the Cabinet Office got together at this secret Information Tribunal, I was not allowed to attend, and the ruling at the end of the day was even 50 years on we could not be told whether there had been an investigation. No information whatsoever could be revealed, because otherwise I might send in thousands of requests on all sorts of people to try find out who had been investigated. That is a fanciful idea. I was asking this because I had very specific intelligence from somebody who was at the heart of the investigation saying Levin was investigated and he died before the end of the investigation”.

That’s an amazing story. It seems that when Britain just enacted the Freedom of Information law, they didn’t really know what they were doing.

“Yes. I was released hundreds and hundreds of documents, no one had gone through them with a fine-tooth comb. Maybe somebody had a quick slick through and thought there was nothing there, but when you went though it ever so carefully you could find all the details: The heavy water transaction, exports of small quantities of Plutonium, Uranium 235, Lithium 6 which can be used in boosted warheads, there were all sorts of stories in there and I don’t think anyone had been through them properly first.

“The one department that did not cooperate was the Foreign Office, who were far more sensitive. When we published our first story the Foreign Office said to me ‘Actually you were correct, but you’ve drawn all the wrong conclusions’. I said ‘How do you know that factually I was correct?’ and they said to me ‘We had a man who went diving into the files, he’s gone through everything, he’s come out with all the files, he’s covered in dust, and I can tell you factually you’re right but you’re drawing the wrong conclusions’. Of course I said ‘Great! I’m now going to put in a Freedom of Information request for all the files that he found in those dusty archives’. About an hour later I got a phone call back from the Foreign Office saying: ‘We had it wrong. There was no man who got covered in dust, there was no archive, it never happened”.

In Israel, The Intelligence community is excluded from the Freedom of Information Act, I don’t know if it is comforting or unsettling to see that even in Great Britain the establishment makes it so hard for journalists to get information on such sensitive subjects.

“Before 2005 we would just find an American angle to a story and put in the Freedom of Information request at the American end. You could probably do the same, because America has a much longer lasting Freedom of Information Act and some states have what they call sunshine rules which means they want the sunshine of truth to shine in, and they have even better Freedom of Information Laws. As a non-American citizen you can still use American FoIA requests. If you can find an American angle on an Israeli story you can put in your request at the American end. You can also do that, by the way, with a lot of European countries, and there has been some great stories that came out by finding a European angle on a story and putting a Freedom of Information request in a Scandinavian country”.

That’s great advice. When did you get the final answer on Levin and how come you decided to print the story on Haaretz this past week?

“Well, when we came to the end of the road we had a situation in which Peter Kelly, our original source, is dead. Once he had realized that the government didn’t want to release anymore he was not prepared to speak with us anymore. He is someone who had been a spook all his life, but he cooperated with us because the government had released all this information so he assumed they would release everything else. As soon as the Cabinet Office refused to release anymore he would not talk to us anymore. So we couldn’t get any further.

“Avner came to Britain last year and we went to Nymen Levin’s son, Peter. We talked to him and got as much as we could out of him, and we came to the conclusion that we are never going to be able to prove one way or the other what happened, that really at this stage the best thing we can do is layout the facts as they are, layout what the MI5 prosecution case would have been and what the defense would have been and leave people to make their own minds up. And also to challenge perhaps the idea that somebody like that, even if they did give information, had been a spy, because they did not have regarded themselves as spies even if they had handed over information. It’s more complicated than that. It’s not like somebody who has been paid to spy.

“So at the end of the day we cannot tell you for sure if he gave information or not. We can say that there was a very strong circumstantial case which you can understand why MI5 would suspect that, but on the other hand MI5 at that stage were very prejudiced against Jews, they wouldn’t let Jews be part of MI5, we know many Jews who were investigated who had absolutely nothing on them. But in this case we know the investigation didn’t come to its end before he died, he died in slightly odd circumstances, and we thought the story deserves to be told even though we couldn’t put a full stop on it, couldn’t dot the i’s and cross the t’s. We thought this is a work in progress but this is what we got, maybe somebody would now come to us and say ‘I can give you the clinching proof’”.

Jones, an investigative journalist and producer, spent most of his career at the BBC. A few months ago he started working as the Investigations Editor at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism a nonprofit news organization. Asked about the differences between the two, Jones replies:

“Obviously you don’t have the resources that I did while I worked on the BBC, on the other hand we don’t have a huge bureaucracy, it’s very much based on what we think is in the public’s interest. I mean I’ve always worked on stories that I thought were in the public’s interest anyhow but the actual ethos of the organization is that we strive for important stories that powerful people don’t want to be told, we’re looking for corruption, we’re looking for abuse of power and that is the whole agenda of the organization. It’s much smaller, it has much less resources but it’s very firmly targeted on the sort of issues that I think need to be covered.

“The Avner Cohen story was a story I worked on before I got to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, but most of the stuff I’m working on now will be published by the Bureau in coordination with newspapers, radio and TV programs, both in Britain and in other countries. And if we find a good Israeli angle on something I’m sure we’ll be in touch with Israeli broadcasters or publications to see if we can work with them. We recently did, for instance, something on the Binary options scandal which is Israeli based. I know The Times of Israel has done some work on the Israeli end of that, we worked on the British end of that”.

Kol-HaAyin is produced by The Seventh Eye and Kol-HaKampus (106FM), the student radio station of the School of Media Studies at The College of Management Academic Studies. The show airs weekly on Kol-HaKampus and is available at the station's website as well as on The Seventh Eye. Music producer: Chen Litvak

This Article was first published on The Seventh Eye. Read it in Hebrew here